Discovering a Satellite

Aug 18, 2022

By Freya Sexton, Lucy Intern

When a group of astronomers set out to catch a glimpse of the shadow of one of Lucy’s targets, the Trojan asteroid Polymele, they had no idea that they were about to discover a whole new tiny world.

The Lucy team was excited. On the evening of March 26, 2022, Polymele was predicted to briefly occult a nondescript 11th magnitude star. Occultations are events in which solar system objects pass in front of distant stars, causing their shadows to fall on the Earth. Amateur and professional astronomers gather to observe these events, setting up their telescopes along a predetermined path. By collaborating, groups of astronomers can use these occultations to ascertain the shape of these celestial objects with a degree of detail unmatched by any other Earth-based observation technique. But occultations have also proved to be a very important part of space missions. While other missions have used occultations to learn about their targets, Lucy is using occultations much more than other missions have. This is in part due to the European Space Agency’s Gaia observatory, which is designed to map the Milky Way Galaxy. Because of Gaia, we now know where stars are located much more accurately than we did before and can use those stars for occultation observations. Because occultations can reveal an object’s precise location, the data they provide about Lucy’s targets can help Lucy’s navigation team bring the spacecraft as close to the Trojan asteroids as is safely possible.

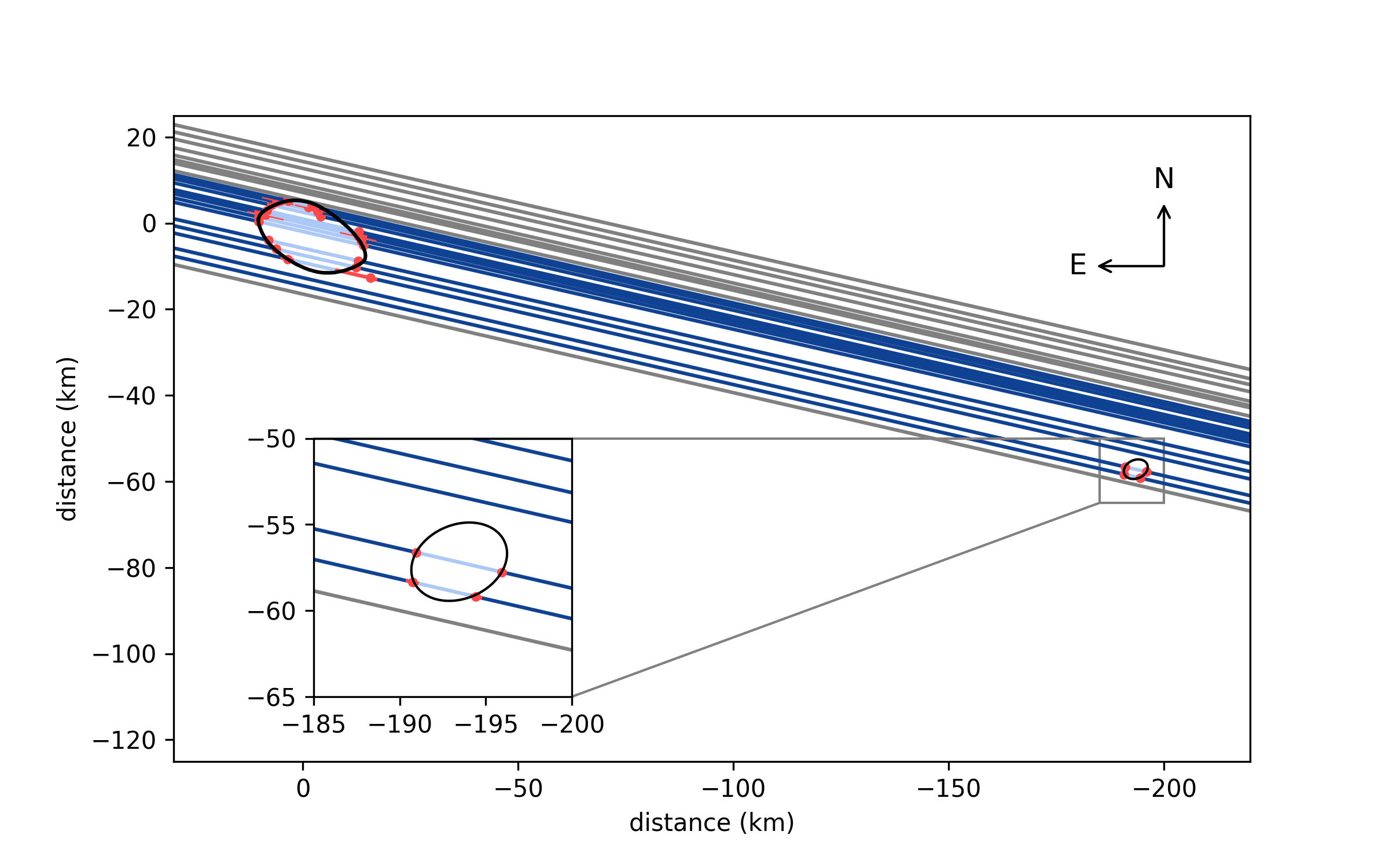

Before any occultation event, astronomers predict where an object’s shadow will fall on the Earth. There is always some uncertainty in the path, but occultation specialists use the best data on the location and motion of the star and occulting body to find the most likely location. The width of an observation path is determined by the estimated width of the object’s shadow and the uncertainty in that path. Parallel lines are then drawn on a map from one edge of the path to the other. These lines indicate where astronomers would need to place their telescopes to record the event from many different vantage points. On March 26th, 26 astronomers spread out across a path that stretched from the Carolinas to western Kansas—bright skies in the western United States kept them from traveling any further.

One team member, Anne Verbiscer, of the University of Virginia, set her telescope up in a dark, open field in Kentucky. She chose the location because it was within approximately 100 miles of her assigned track. The field happened to be on private property, so the day before the occultation was to occur, Verbiscer called the property owners to ask permission to use their field. The kind couple was more than happy to loan their field for such an amazing occasion and extended a warm welcome to Verbiscer upon her arrival. Shortly after she finished setting up her telescope, Verbiscer was greeted by the couple, who approached without flashlights out of respect for the need for total darkness. As she recorded the event, the couple waited patiently and then enjoyed a fantastic tour of the night sky via telescope.

The Lucy team astronomers encounter generous and hospitable people at occultation events all around the world. Many are just as warm and as welcoming as the two that Anne Verbiscer encountered in March.

“The people really are my favorite part of what I do,” says Verbiscer. Not only have they opened their properties and homes to the team, but many have also shared food and laughter. Some have even gone above and beyond in helping the team accomplish their tasks, especially when it comes to harsh weather conditions. I’ve been all around the world for these events and have observed in almost every type of weather imaginable. I’ve been drenched in sweat, and I have held a tarp up against bitterly cold winds for 45 minutes to protect a telescope,” says Verbiscer. She describes a time when strangers brought a sheet of plywood and a tarp and assisted her and other team members in using them to protect against fierce and biting winds. Because of the kindness of these strangers, the occultation team was able to successfully record the event with no damage to their equipment and with little exposure to the icy, cold winds.”

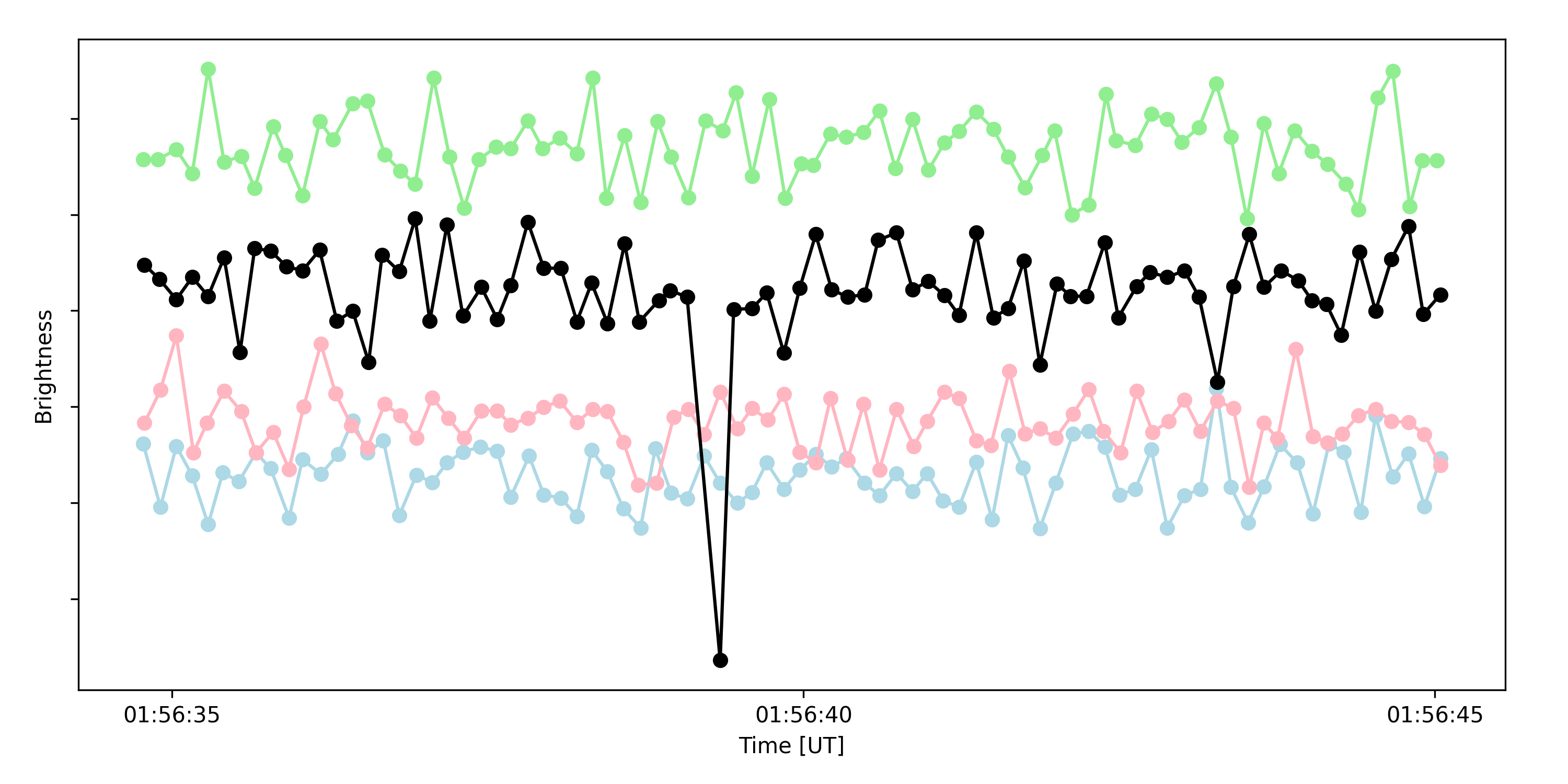

On the night of March 26th, the team experienced unusually fair weather for Spring in that part of the United States. They were treated to clear skies, which allowed them to capture beautiful images of Polymele as it eclipsed a star. Of the 26 teams involved, 16 witnessed an occultation.

It is normal that not everyone gets to see the star disappear when the object passes in front of it; in fact, it is planned. This is because the predetermined viewing points are designed to measure the size of an object. Telescopes are often separated by many miles and are sometimes even located in different states or countries. By looking at the compiled data and determining who could see the occultation and who could not, astronomers can get a pretty good idea about the size, shape, and, by combining multiple observations, even the orbit of an object. “On that night, I didn’t see the star blink out,” says Anne Verbiscer. “The data I collected did have an important role, however. It provided a constraint, which allowed us to gain a better understanding of what we were seeing.” Verbiscer explains that her vantage point marked the northern edge of Polymele, which provided an important piece of the puzzle that the team was attempting to put together.

Later that night, as the team celebrated a successful campaign and discussed their observations, one team member noted that the occultation occurred a little later than anticipated; however, no one thought much of it at the time. It wasn’t until a couple of days later that Lucy’s occultation leader, Marc Buie announced that those who had witnessed a delay in the occultation had done so because the object they were observing was not Polymele. The team had discovered a new asteroid! As word of the discovery spread through the Lucy Team, so did the excitement. The combined efforts of the astronomers and their unfailing teamwork had led to the discovery of a satellite orbiting Polymele!

“It truly is a team effort,” notes Anne Verbiscer. No matter the campaign, not only does the team work effectively to get each job done, but each member genuinely cares about and looks out for the others while in the field. The group usually ends each event with a regrouping of the team- an opportunity, not only to celebrate successes and reflect on any complications that arose during the night but for the team to make sure that every member is accounted for.

Now, as Lucy makes its way back towards Earth for its first Earth Gravity Assist (EGA) in October, the Lucy occultation team is back in the field, collecting additional data about Lucy’s future targets. More information about current and future occultation campaigns can be found here.

Thanks to the hard work of the Lucy Team astronomers and a bit of luck, Lucy now has one more asteroid to observe!

Banner Image: Some of the telescopes used by SwRI for the occultation campaigns being checked out prior to deployment.